The increasing percentage of distributed energy resources (DERs) brings a degree of uncertainty in bulk power system planning and operations. Additionally, it introduces an element of uncertainty with regard to distribution planning and operations, especially with regard to the dynamic behavior of DERs in juxtaposition with the behavior of induction motors. Legacy interconnection standards such as IEEE Standard 1547TM-2003 allowed for DERs to trip from the distribution system very rapidly upon the occurrence of a voltage or frequency event. In most cases, DERs were allowed to trip almost instantaneously if their terminal voltage fell below 0.88 pu. Such an operating practice was primarily driven by distribution operation and safety practices at the time when DERs were still a relatively low percentage of the mix. Distribution operations preferred to have a passive distribution network while responding to system events. However, as the percentage of DERs increases, this restrictive operation model could result in further issues to be resolved during system events. Additionally, the large loss of active power (due to trip of DERs), especially when the system requires it the most, could cause cascading impacts on the power system.

A Moving Target

A Moving Target

Recent updates on the IEEE Std 1547TM have continually introduced requirements for wider voltage and frequency ride-through capabilities and trip settings for additional smart inverter functionalities such as dynamic voltage support. Currently, the threshold values and timers related to the trip settings have a range of applicability; the degree to which the capability of the smart inverter functionalities is used is left to the decision of the respective electric utilities in whose footprint the DER interconnects. Thus, the nature of the interconnection process and the continual evolution of the standard can create confusion. Although a more recent standard may be available, unless the electric utility requires the use of the recent standard (as detailed in the corresponding interconnection requirements), there can be an added uncertainty from the perspective of the planner/operator regarding which standard is being followed for legacy and newly interconnecting DERs.

Since the behavior of an increased percentage of DERs has an impact on the bulk power transmission system, technical interconnection requirements for DERs should have input from transmission planning and operation engineers. Major points that need to be addressed in the technical interconnection requirements relate to

-

- value of voltage thresholds at which the DER enters momentary cessation,

- value of voltage thresholds at which the DER’s trip timers activate,

- value of the time at which the DER would trip after activation of the trip timers,

- requirement for activation of smart features such as dynamic voltage support and/or frequency support, and

- priority order (whether active or reactive power is used) for current injection.

Note here that although information related to requirements (2) and (3) above is beneficial and important, they are not specifically denoted in the IEEE 1547 standards. The IEEE 1547 standards only specify trip clearing times. In this blog, by comparing three scenarios with incrementally different DER fault behavior, I will illustrate the need to consider transmission system impact of DERs while defining DER interconnection specifications. The focus is predominantly on inverter-based DERs, although parameters related to trip and voltage support apply equally to synchronous DERs.

A Look to the Future

Consider a future scenario with high DER penetration spread out over numerous transmission substations in a balancing area as shown in Figure 1. Although the DER magnitude at any one substation can be considered to be low by transmission loading levels, the sum total MW of DERs in this balancing area amounts to approximately 6.5 GW, which is 1.5 GW greater than the total load in the area! With such a large presence of DERs, adherence to a narrow region of operation could have an unfavorable impact on the bulk power system.

Figure 1: Spread of DERs over numerous transmission substations in a balancing area

Table 1: Details of three scenarios studied to illustrate DER impact on bulk power system

| Scenario | Applicable IEEE standard | Momentary cessation voltage threshold (pu) | Trip voltage threshold (pu) | Time to trip (s) |

| 1 | 1547 – 2003 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.16 |

| 1a | 1547 – 2003 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.16 |

| 2 | 1547 – 2018 Cat II | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.16 |

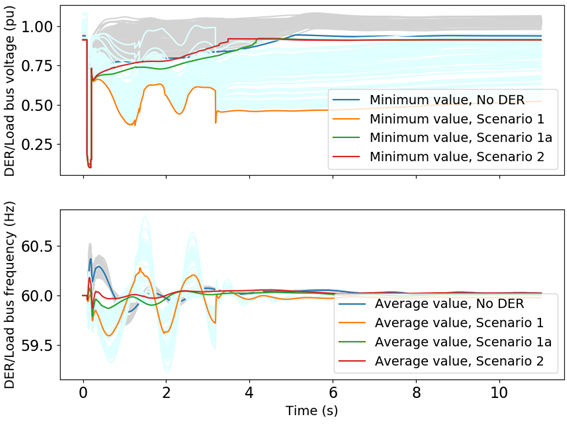

IEEE 1547-2018 includes a recommendation for Category II DERs to lower both the momentary cessation threshold and the trip threshold relative to the specifications/recommendations of IEEE 1547-2003. What follows is an example of the benefits of the new version’s values. Scenario 1 in Table 1 is structured to set all 6.5 GW of DERs in the system to go into momentary cessation at a value of voltage below 0.88 pu and trip if the voltage stays below this value for more than 0.16 second. This conservative time threshold (in relation to IEEE Std 1547TM) has been intentionally considered for legacy DERs. Additionally, the DERs are assumed to not have the capability of smart functions like dynamic voltage support and frequency control. The response of the system to a contingency event from the TPL – P7 category is shown in Figure 2 both without any DER and after addition of DER.

Figure 2: Comparison of system response (bus voltage (top) and frequency (bottom)) without and with DER

Even before the addition of DER, there is evidence of slow voltage recovery occurring due to the stalling of single-phase induction motor loads, but the recovery of voltage is within the area’s voltage recovery criteria. With DERs operating only in a narrow voltage range, upon occurrence of the fault all DERs cease to inject current as the voltage falls below 0.88 pu. This operation by itself would not impact the bulk power system, as the power injection to the network would be low due to the low voltage. However, upon fault clearing, due to the induction motors stalling, the voltage does not recover above 0.88 pu. As a result, even after fault recovery, the DERs remain in their momentary cessation operation mode. This behavior has a large impact on the bulk power system as it results in the loss of 6.5 GW of generation at a time when the system needs it the most. The voltage remains depressed below 0.88 pu for more than 0.16 second, resulting in all DERs tripping. The resulting voltage trajectory could now result in depressed voltage levels across the entire local load area.

An immediate mitigation mechanism is to lower the momentary cessation threshold from 0.88 pu to 0.50 pu as done in scenario 1a. Now, although DERs go into momentary cessation during the fault, the voltage recovers above 0.50 pu upon fault recovery, resulting in resumption of active power injection from DERs with a beneficial impact on the voltage recovery. Although around 2 GW of DERs still trip since the voltage at some locations does not recover above 0.88 pu within 0.16 second, the entire system voltage recovery is now within the area’s criteria. This response and behavior could still be a cause of concern, however, as around 2 GW of active power is now lost. The next step in mitigation is to also lower the voltage trip threshold to 0.50 pu as denoted in scenario 2.

This lowering of both the momentary cessation and the trip threshold is one of the essential modifications that was recommended in IEEE Std 1547TM-2018 for Category II DERs, and its positive impact is observable from the study results.

A Path Forward

Stalling of single-phase induction motors upon occurrence of a fault is known to have an impact on transmission system voltage recovery, a phenomenon termed fault-induced delayed voltage recovery (FIDVR). The low voltage caused by transmission faults can potentially induce single-phase induction motors to stall and if not tripped, can delay the recovery of voltage upon clearance of the fault. Preliminary research results indicate that the provision of adequate dynamic voltage support from DERs can help some or many single-phase induction motors to re-accelerate after clearance of the fault, thereby improving the voltage trajectory.

As illustrated by the above example, potential recommendations/best practices that can be followed for future DER interconnections from the perspective of a transmission system are provided below. (Additional information can be found in a soon-to-be-published 2021 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting paper titled “Deriving IEEE Std 1547TM Settings that Benefit Transmission System Dynamic Behavior.” Please contact the author to obtain a pre-print.) Recommendations include:

-

-

- Incorporation of IEEE Std 1547TM-2018 Category II and IEEE Std 1547TM-2020 Category III settings which provide longer ride-through capability for DERs.

a. Results in the reduction of MW of DER generation that will trip for a transmission fault - Incorporation of IEEE Std 1547TM-2018 Category II settings with lower momentary cessation and voltage trip thresholds. This will require renewed UL 1741 SA certification.

a. Results in reduction of MW of load that will trip for a transmission fault - Enabling of dynamic voltage support (at the moment optional in IEEE Std 1547TM-2018).

a. Results in reduction of MW of load and DER generation that will trip for a transmission fault

b. Results in improved voltage recovery trajectory

- Incorporation of IEEE Std 1547TM-2018 Category II and IEEE Std 1547TM-2020 Category III settings which provide longer ride-through capability for DERs.

-

Implementation of these best practices must, however, be tempered with increased coordination across the transmission-distribution interface. DER operational features that may seem to provide increased benefit to the transmission system may result in inadvertent consequences within the distribution network. The growing field of co-simulation should be leveraged (without sacrificing engineering judgment) to gain further insight into impacts that DERs can have on the bulk power system.

Deepak Ramasubramanian

Technical Leader, EPRI

Hi Deepak, I really enjoyed reading your blog. Quick question: Does the IEEE Std 1547-2018 recommend lowering the terminal voltage to a particular value (here 0.5pu)? If not, please let me know what factors were involved in selecting “0.5pu” as an alternative.

Would appreciate a quick post on how you see IEEE 2800 helping in this area; key differences, benefits, drawbacks (if any)?

Hi Rasik. Thank you very much. IEEE Std 1547-2018 has multiple categories. For Category II and Category III, the momentary cessation threshold is recommended to be lowered to a default value of 0.5pu. There is a range that can be used here as per standard, but we chose 0.5pu in our study as it was most conservative from this range. Hope this helps? Thanks.

Hi Paul. Thank you very much for your comment. One key distinction is that IEEE P2800 is focused on bulk power system connected inverter based resources while IEEE 1547 focuses on distribution system resources. That being said, there are complimentary aspects involved. On this note, I would like to kindly refer you to this previous ESIG Blog Post (https://www.esig.energy/ieee-p2800-enhancing-the-dynamic-performance-of-high-ibr-grids/) that my colleagues from EPRI wrote about the IEEE P2800 standard. Hope this helps? Thanks.